Introduction

The Meijers Committee and the Amsterdam Centre for European Law and Governance (ACELG) of the University of Amsterdam (UvA) organized on 11 July an online seminar on the enforcement of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA).

Media pluralism reveals a complex puzzle in the EU’s legal order. While media pluralism features among the most important values of the EU, the Union lacks an explicit competence to regulate the media and media as a field of EU policy is absent from the Treaties.

In September 2022, the European Commission proposed the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) to promote media freedom and pluralism. The initiative seeks to address contemporary practices which threaten the economic and democratic function of media in the EU. The proposal also contains several enforcement mechanisms. It is, however, highly questionable whether these mechanisms improve the effectiveness and credibility of enforcement of media law and policy in the EU.

This online seminar brought together policymakers, academics, and members of the EP to discuss the question how the EMFA and media law and policy could be better enforced across the EU. The participants drew on expertise from both media law and EU competition law that can offer tools or examples to safeguard media pluralism in the EU.[1]

Panelist contributions

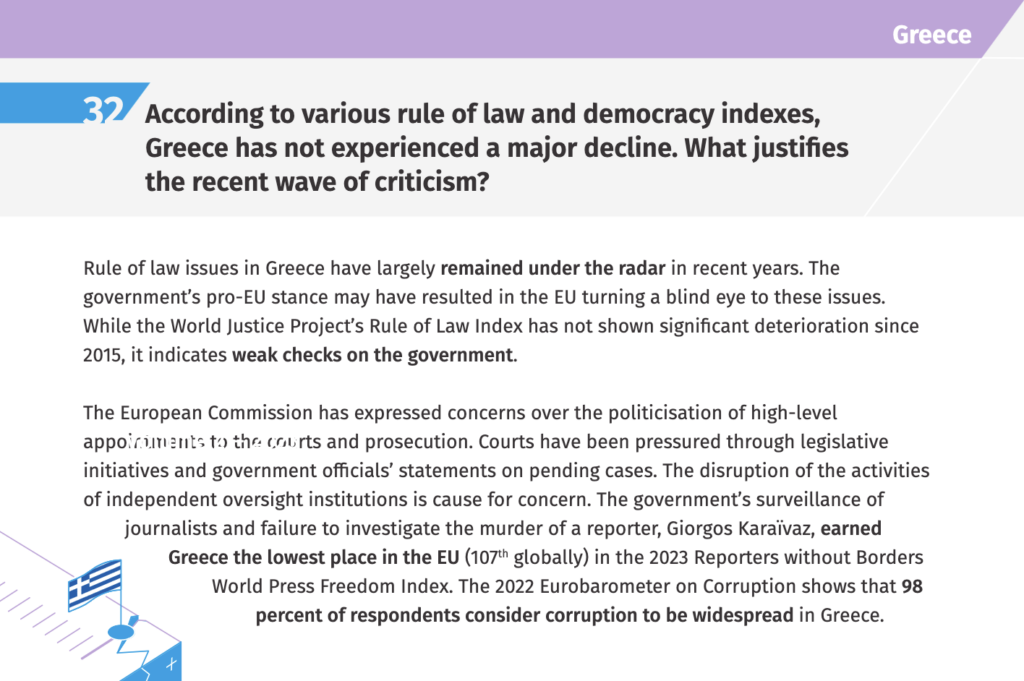

Daniel Freund (MEP Greens) emphasized the importance of protecting journalism and journalists which comes with the rule of law backsliding in EU Member States. He mentioned that the EP is closely following developments that could undermine media pluralism in the EU, such as the abuse of spyware and attacks on independent news media and journalists. Noteworthy are several EP measures which aim to safeguard media pluralism, such as the PEGA report (investigating abuse of spyware (against journalists)).

Developments like state capture of media in some Member States threaten European interests of democracy and rule of law. With the EMFA proposal, the European Commission has exactly tried to accommodate these growing concerns. LIBE and CULT committees will soon vote on the EMFA.

According to Freund, the EC should go further to address the situation in Hungary. On top of the option to launch an infringement procedure, the Commission should use the available competition law tools. But how to address the concerns by States with more pluralist and free media who feel threatened by these strong tools? In general, what tool is to be used in each circumstance is contingent on the severity of the threat to media pluralism in the Member State at hand. Freund stressed that it is about finding the right safeguards.

–

Dr. Konstantina Bania (Geradin Partners and Brunel Uni) started with explaining the symbiotic relation between RoL and media pluralism: on the one hand, public powers act to protect media pluralism (see EU RoL definition), but on the other hand, pluralistic media should hold authorities to account (see examples in EC RoL reporting).

She noted that EC RoL reporting is not the only tool at the disposal of the EC to protect media pluralism.

Media pluralism is a very complex issue (complexity is reflected by multi-dimensional nature of media pluralism: supply diversity, content diversity, exposure diversity) in which the EU has significant limitations to regulate. Yet, she emphasized the importance of the cross-sectional clause in Treaty (art 167(4) TFEU) which stipulates that the EU should consider cultural diversity, incl. media, when implementing other Union policies (such as internal market and competition policies)

But how can competition law enforcement consider media pluralism? In the field of anti-trust and merger control, Bania observed that EC has been focusing on prices. But in media market, price is not most important parameter of competition, if at all (as much media we consume is for free…) Bania regretted that the EC refrains from discussing other important factors such as quality, originality, and variety, which happen to be very important in the media market and for media pluralism. Also, in the field of state aid control, Bania believed that the EU had potential to do more. As one example, she posed the rhetorical question whether public broadcasters shouldn’t be independent from the government.

Bania discussed the specific acts to safeguard media pluralism before turning to EMFA, such as the DMA and DSA, in which she sees possibilities to level the media market and hence media pluralism. She believed the EMFA is a notable initiative, as it also tries to level the playing field and it tries to regulate across the board: governments, but e.g., also obligations for platforms.

Bania then focused on two intertwined issues: (a) whether the EMFA is in the position to address the regulatory asymmetries between platforms and the rest, (b) whether the EMFA can indeed apply “without prejudice” to the rules that have recently been adopted to regulate the platform economy. In that respect, she made a few comments on the DMA, the P2B Regulation, and national prominence rules. Her main argument here was that if we try to reform the framework to inter alia make platforms (and others) more accountable to users, we need to ensure that tensions with other regulations are avoided to prevent clash (and perhaps pre-emption).

–

After Bania’s more substantive comments, Dr. Judit Bayer (Uni Münster) and Dr. Kati Cseres (UvA) delved into the actual enforcement of the EMFA and more generally how media law and policy could be strengthened across the EU. Specifically, they talked about how to improve the enforcement of the EMFA and more generally media law and policy, and what role competition authorities could play in this.

They started their presentation by stating that media pluralism is threatened by media capture (in illiberal member states) but also new media environment dominated by platforms (the latter also creates problems in liberal member states). This creates additional regulatory challenges. They noted that there are many different stakeholders involved and their relationship seems to be characterized by mutual distrust. Media owners mostly don’t trust the State, while media owners in some Member States have indeed very close (and unhealthy) relationships with politicians and big investors. Generally, all stakeholders distrust the EC because of its supranational sanctioning powers which could intervene with national media governance. It leads to a chaotic situation where the enforcement of media law is difficult.

According to Bayer and Cseres, the proposed enforcement framework in the EMFA however does not change much. The EMFA merely establishes friendly cooperation, rather than actual enforcement structured around the role and tasks of national regulatory authorities (NRA). It therefore does not really improve the effectiveness and credibility of media law and policy in the EU. This is particularly the case in situations of systemic non-compliance by national regulatory authorities or Member States (e.g., in Hungary).

Bayer and Cseres recommended an alternative way of how the EMFA is to be shaped. Their governance framework should create a transparent enforcement mechanism in which the different stakeholders control each other, like a system of checks and balances. Their framework should contain three essential elements: a) all decisions of the Board and Commission should be supported by a wider consensus of experts and stakeholders; b) post-merger assessment of media concentrations c) the Board’s opinion can ultimately trigger an extraordinary market investigation by the Commission which may lead to an infringement procedure within a specific deadline after a defined process of dialogue. They stressed that this recommended framework could address the systematic non-compliance by Member States and create stronger ties between the stakeholders.

Finally, Bayer and Cseres explained how the role of competition authorities, “with court-like functions” could be reconsidered in dispersing economic concentration, defending media pluralism, and enforcing the EMFA. Besides their role in safeguarding undistorted competition within the internal market, Bayer and Cseres mentioned that these competition authorities also defend effective judicial protection (Article 19 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR)) relevant to both defendants and victims in the competition context. Moreover, Bayer and Cseres highlighted recent EU case law, in which Article 2 values applied to the enforcement by competition authorities. In these decisions, the Courts emphasized the relevance of mutual trust and sincere cooperation in cases when competition authorities must cooperate with other administrative authorities responsible for other regulatory fields.

–

Attendees

30 people have attended the online seminar, with different backgrounds ranging from EU and Member States officials to lawyers, academics, media, journalists, and civil society.

–

Amsterdam, 18 July 2023

[1] NB: the search for alternative pathways to enhance media freedom in the EU is in line with the Meijers Committee’s earlier work on media pluralism. In our comment CM2113, we assessed amongst others avenues in which media freedom intersects with free and fair elections (note also CM2302), state aid and public broadcasting, state advertising as state aid, and specific services sectors.